To the Max: The History of Torker 1975-1984

This is my attempt to compile an accurate history of Torker. I’ve been wanting to do this for years, but only got serious about doing it in mid-2008. My background as a journalist reporting on the bicycle industry, life-long love of cycling and deep interest in Torker as a company as well as the people behind it and its products, hopefully, qualify me to pen this brief history.

I referred to a collection of advertisements and articles found in various hard and digital copies of Bicycle Motocross Action and BMX Plus magazines, conversations with company founder John Johnson, former Torker racers and factory employees who were there at the time and my observations and measurements taken from Torker frames and products.

This is a history of Torker for the collector or BMX historian. It starts at Torker’s beginning in 1975 and finishes at its end in 1984. I tried to include as much information as I could with a focus on product development, business relationships and the company’s ups and downs. I hope in the future to add more information about Torker’s final months under the Johnsons and try to understand why the Johnsons shuttered the company.

This history is in no way complete and is open to corrections and additions. Feel free to send me documented corrections. I will update and correct as needed.

I’d like to thank those who helped with this: John Johnson, Steve Rink, Harold “McGoo” McGruther, Doug Olson, Howie Cohen, Dennis Dain, Brain Ramosinski, Eddy King, Bob Osborn for his photos and for producing the greatest BMX mag ever—BMXA, Bob Hadley, Craig “Gork” Barrette and Mike Aguilera.

Photos are from BMXA, BMX Plus and other undocumented sources. Please contact me if you would like credit or would like to have them removed. —MG

The Beginning Before there was Torker, there was a small family-owned and operated company called Texon, operated out of the Johnson Family garage in Anaheim Hills, California. Founded in 1975 by John Johnson, Texon included John’s wife Doris and their sons Steve and Doug. It’s reason for being was to build a handful of prototype BMX frames.

The company was soon renamed Johnson Engineering, a name that would later appear in tiny type at the bottom of the earliest Torker headbadges. Around 1976, it was renamed again, to Torker. “Steve [Johnson] didn’t like Texon, so he renamed it Johnson Engineering. Then, he came up with Torker, a name that no one was using. He took the name from the work Torque. I think it was a good name,” John Johnson said.

Harold “McGoo” McGruther, who raced for Torker between 1979 and 1981 and worked for the company from 1982 until 1984, said the Johnsons were interested in BMX bikes from the beginning.

“John made the company’s first 4130-chromoly prototype in 1975 from tubing salvaged from a small airplane fuselage. John was an experimental airplane test pilot for the FAA so he knew chromoly and fab work as well as anyone during that era,” McGruther said.

“They made the original Peddlepower frame as a job shop on a wooden jig in their family garage. Peddlepower went on to become Powerlite,” he added.

Steve Johnson is often the family member credited with seeing the potential in BMX, designing the frames and building the brand.

“Steve and his mother ran the company,” said Howie Cohen, founder and owner of Everything Bicycles, one of Torker’s earliest distributors. “Steve did design and sales and his mom handled the bookkeeping. I never had any dealings with his dad,” he said.

Almost from the beginning, Steve Johnson was Torker’s president, front man and later team manager. Although he certainly contributed to Torker’s product development, but he didn’t come up with the early frame design.

The first BMX frames the Johnsons made were for Steve Rink, the owner and founder of the Peddlepower Cycles in Orange, California, and later Powerlite.

Those frame, built by Texon in the Johnson’s garage in 1975 and nicknamed the Rink’s Raider, featured what would become Torker’s trademark twin top tube. According to many, the design was Steve Johnson’s. But the truth is it was Rink who brought the design to the Johnsons.

“I knew Steve’s dad John from the FAA. I did flight tests and knew him through that. He’d come into the bike shop [Peddlepower Cycles] and I told to him I was going to do a frame. He wanted to help out, so I started working with John. I’m not sure when Steve got involved,” Rink said.

“John only made the first Peddlepower frame. Rink’s Raider was a nickname, but it was never sold under that name.

“I came up with the twin top tube design because it was easy to make. The top tube and seat stays were one tube and needed just one simple bend. Construction-wise it was easy to make,” Rink said.

Although the frame was a snap to build, Rink said it had a big problem.

“It was a big frame. It was good for pro riders, but kids couldn’t ride it. That’s why I came up with the single top tube Peddlepower frames. John and I were good friends and there were no problems between us when he started Torker, using the twin top tube design,” Rink said.

John Johnson remembers his involvement with Rink with a little more detail.

Youngest son Doug was racing BMX in the early-1970s on a bike he bought from Peddlepower and he wanted something lighter weight.

“Steve Rink got us started in this. Our son Doug was racing over at the Lincoln Avenue race track. Most kids were racing stripped down Stingrays. Doug thought it was too heavy, so he asked me to build one. I thought I could build one out of aircraft tubing,” he recalled.

“I talked to Steve and he gave this frame with a double top tube. I don’t know where he got it. I used that to build the jig. I built a jig on an old wooden school door. I built four of these. I took them to a local welder to have them tacked up and then welded. At the time, we didn’t have a heli-arc welder yet,” Johnson said.

The first frame built for Doug Johnson had some of the same features as later Torkers would, but it was crude.

“Frame number one was mild steel and the top tubes were cut and welded to the seat stays. They were two-piece, not the one-piece design we did later. I didn’t have a way to bend the tubes, so I cut them,” Johnson said, adding that he still has the frame today. “It’s pretty well beat up after all these years.”

After that first frame, Johnson built the Peddlepower prototypes. He couldn’t recall exactly how many he built, but thought the number was between eight and 50.

“I built two, then four, then eight. We kept doubling the number. Around this time, Steve [Johnson] got involved. He wanted to start his own business. I was working full time for the FAA as a test pilot and engineer and building frames at night and on the weekends. I let Steve take over.

“We were in the garage and had a Southbend lathe and a Bridgeport mill. Steve bought a heli-arc welder right away,” Johnson said.

Before long, their differing goals and visions for the company led to a split between Steve Johnson and Steve Rink, John Johnson said. “Steve wanted to sell the bikes under the name Johnson Engineering. Steve Rink didn’t like that name and wanted to use his name, Peddlepower. Steve started making bikes for himself and then came up with the name Torker,” Johnson said.

John’s wife Doris also is credited with much of Torker’s early success. Besides running the Torker offices, Doris managed the Torker team. “Much of the credit for the success of the Torker team belongs to Doris Johnson. She was the team mom and tour rig driver. Everyone loved her,” McGruther said.

Torker Factory Team racer Mike Aguilera agreed. “Doris was the team mom who cooked, cleaned, did laundry for all of us boys while on tour,” he said.

In 1979, Doris drove the team to races all over the country in a motor home. Son Doug would later run clothing maker Max, Torker’s sister company. “Doris and I worked for free, but everyone else got a pay check. We worked 14- and 16-hour days and on weekends. I continued to work at the FAA full time until I retired in 1981,” Johnson said.

Torker Takes Off Johnson Engineering became Torker BMX Products sometime in late-1977 and officially introduced its first frame and bike in mid-1977. As late as August 1977, the company was running ads for its blue or red Torker frame in Bicycle Motocross Action magazine (BMXA) under the name Johnson Engineering.

It was in late-1976 that the editors at BMXA learned of Johnson’s plans to launch a Torker frame. A photo of the new bike appeared in the February 1977 issue.

BMXA then published a product test of the Torker in the October 1977 issue. The staff described the frame as being made entirely from TIG-welded, aircraft-quality, 4130-chromoly tubing. It was called the Torker MX. Torker would later change the name to Big Bike after it introduced a second, smaller frame called the L.P. around May 1978.

Touting its “superb engineering” and “flawless handing characteristics,” BMXA publisher Bob Osborn called the Torker MX “The Husquavarna of motocross bicycles.”

As if in agreement with Steve Rink, the BMXA staff said the MX worked great for bigger riders and those looking to throw in a little style while in the air.

The BMXA test bike was equipped with Speedo forks, which bent during testing. Torker’s first forks were in development at the time of the test. They would hit the market along with a variety of other Torker-branded components and accessories later that year.

Much of the BMXA article focuses on the technology and engineering Torker put into the frame.

Besides 4130-chromoly tubing, the frame featured double “fish scale” gussets at the head tube and Torker’s ubiquitous twin top tube design, which, according to BMXA, nearly eliminated flex at the bottom bracket.

It also was one of the first BMX frames to be stress relieved. Varco International baked Torker’s frames at 1,000º Fahrenheit for two hours after welding to relieve, “internal stresses, and, in effect, make it one continuous piece of metal, as opposed to a bunch of pieces with a bunch of welds holding them together,” Osborn wrote.

The MX frame had a 70-degree head tube angle, a 37-inch wheelbase and when built with number plate and pads the bike weighed 25 to 27 pounds. It was available in chrome, blue or red (Osborn wrote that it looked more like maroon.), powder epoxy, which was electrostatically applied by Aquarian, which also did epoxy coating for JMC.

According to Chip Bowers at C4 Labs, a company specializing in refinishing bicycle frames, the epoxy process was similar powder coating. “The frames were painted in a way that can be considered powder coating. Now, most powders are polyester based instead of epoxy,” he said.

The MX came with Cheng Shin tires, steel Araya rims, Sunshine black alloy front hub and Bendix coaster brake, 105-gauge spokes, Takagi 7-inch cranks, KKT pedals, Addicks sprocket and spider, Ashtabula single-clamp stem, box handlebars, Elina Super-Pro padded saddle and Speedo forks.

Torker’s first ad ran in December 1976 in BMX Weekly. The stickers on the frame featured the red Torker MX/Johnson Engineering headbadge, lightning-bolt logo down tube stickers and either two “Chrome Moly” stickers or nothing on the seat tube. Yellow headbadges appeared on some frames, as well. The retail price of the bike was $210 on the West Coast and $220 on the East Coast. The price difference was due to the cost of shipping.

The MX took what several collectors describe as an “odd size headset.” This odd size is likely the standard road size headset that fit frames with 30.1 mm I.D. head tubes. Many companies used these early on. Some MXes also had un-drilled brake bridges. Serial numbers on the frames show month, year and production number. For example, T877128—8 = August, 77 = 1977 and 128 is the production number.

Torker introduced pads, box-style handlebars and a few pieces of clothing, such as hats and T-shirts later in 1977.

Kevin McNeal, Torker’s first big-name sponsored rider, began racing for the company that year, too. Riding a Torker MX, he became California Champion and won the NBA/Mongoose Grandnationals.

A New Design Just one year after making it’s debut, the MX was facing obsolescence. There was a new kid on the block and it had a faster, sleeker and more modern look. It also fit a wider range of riders. Torker’s new low-profile L.P. frame, or minor variations on it, would become Torker’s mainstay frame until it’s bankruptcy in 1984. The gangly MX, now renamed Big Bike and later updated with rear-facing dropouts and a BMX-size (32.7 mm I.D.) head tube, but its appeal was limited to larger riders.

Production of the L.P. seems to have begun in or around May 1978. The frame and the new Big Bike are featured in a never-produced or distributed Torker Dealers Catalog that was put together in the spring of that year and with a cover date of July 15, 1978. Although there are no detailed descriptions of any of Torker’s frames there are four new frames featured in the catalog. Those frames include the chromoly G.T. Big Bike, mild steel Big Bike, chromoly L.P. (Low Profile) G.T. and mild steel L.P. Each was offered as a frame and complete bike. The suggested retail price of the G.T. Big Bike was $84.95, the L.P.G.T. was $89.95 and both mild steel frames was $59.95.

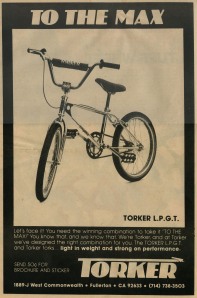

The L.P. appears to have made its public debut in an advertisement in the June 1978 issue of BMX Weekly then later to a broader audience in the August 1978 issue of BMXA. (Steve Rink’s low-profile, single top tube Peddlepower SR frame made its debut in the Feb. issue of BMXA that year.)

At the heart of the L.P. ad is a photo of a complete bike Torker called the L.P.G.T. It has a European bottom bracket shell, Shimano Dura-Ace three-piece cranks, KKT Rat Trap pedals, new Torker alloy handlebars, MCS 6-bolt stem, steel seat clamp, Cycle Pro Snake Belly skin-wall tires, alloy wheels and Torker forks. According to the Dealers Catalog, the retail price was $185.

This is perhaps the first ad for the new L.P.G.T. as it appeared in the June 1978 issue of BMX Weekly.

The new L.P. had an 18.5-inch top tube, dual head tube gussets, round brake bridge (like the MX), relaxed 64-degree seat tube angle and was available in chrome, red, blue, black, white and, according to the Dealers Catalog, gold. The only L.P. frame to appear in any ads through the end of 1978 had a European bottom bracket shell. It’s unclear if the L.P. also was available with an American bottom bracket shell. This, however, is unlikely due to the fact that L.P.G.T. was designed for smaller riders while the Big Bike was designed for larger riders and therefore spec’d with an American bottom bracket shell. At that time, many smaller frames were sold only with a European bottom bracket shell.

The sticker pack on the L.P.G.T. in the ad was the same as the one used in 1977 on the MX. The logo on the new vinyl pads was in the original Torker logo font—the lightning bolt logo minus the lightning bolt.

Serial numbers for Torker frames made through 1978 were on the bottom bracket shell. With its new name, the Big Bike had serial numbers that ended with a “B.” And, although I have yet to see a confirmed 1978 Torker L.P. frame, it is assumed the serial numbers on those ended with “L,” as they would in 1979. With the introduction of the L.P. and Big Bike, Torker started using a new serial number system. (For more on this, please read the Torker Serial Number Guide on this Blog.)

In most photographs, these frames had two “4130 Chrome Moly” stickers on either side of the seat tube. By 1979, chromoly Torkers had only one “4130 Chrome Moly” sticker placed in the center of the front of the tube. Forks at this time were not drilled for brakes and had lightning-bolt logo stickers.

According to John Johnson, however, the frames were not 100-percent chromoly. “We used mild steel for the headtube, bottom bracket shell and all the flat parts like the dropouts and gussets. There was no advantage to using chromoly on those parts,” he said.

The 1978 Dealers Catalog, the only remaining copy of which belongs to John Johnson, mentions three products that were in development at the time—a Torker Double stem, a mini Torker and the EK Special. Eddy King (EK) was and amateur racer who was co-sponsored by Torker at the time. He would later become one of the Torker Factory Team’s best-known racers.

The Salad Days The years between 1979 and 1981 were good for Torker. The company had begun sponsoring races, including local and national events and up-and-coming Expert racers such as Doug Davis, Mike Aguilera and Eddy King in 1978. Torker cosponsored King while he was racing for Wheels ‘N Things and signed him as an amateur to its Factory Team in the fall of 1978 at the U.S. Nationals.

During this period, Steve Johnson established very good relationships with the editors at BMXA and BMX Plus!. Torker was advertising consistently in both magazines and in turn received a lot of coverage in its pages. Many company chiefs and racers at the time, claim that the amount of coverage your company and racers got in BMXA was directly related to the amount of advertising you did. This does not, however, diminish the fact that Torker was a leading BMX company with one of the country’s best factory teams.

Not long after King joined the team, Torker began marketing a 3.5-pound L.P. with a European bottom bracket called the E.K. Replica, after Eddy King. The frame took its place at the top of the line and, despite the fact that it was basically an L.P. with a European bottom bracket shell, was priced $2 to $3 higher than the standard L.P.

Other new products that year include an aluminum and chromoly, six-bolt stem; chromoly mini and 26-inch cruiser forks and at least two complete bikes—the Maxflyte and Torkflyte.

The L.P. and Big Bike were available in 4130-chromoly and mild-steel versions, giving consumers the ability to buy a Torker at a lower price. The frames were identical except for the tubing material.

BMX mail order giant Wes’ BMX in 1981 listed the mild-steel L.P. frame for $69, while the L.P. cost $99 for painted and $107 for chrome. The lower-price, mild-steel frames lack the “Chrome Moly” seat tube sticker and have an “M” at the end of their serial numbers. Mild-steel Big Bikes had “BM” at the end of the serial numbers, while the mild-steel L.P.s had “LM.”

By the end of 1979, the Big Bike appears to have been removed from the Torker catalog, replaced by the L.P. Long, which had serial numbers ending in “0” for chromoly frames or “0M” for mild steel frames.

That year, all Torker frames were available in chrome, black, blue, red or white and had a new sticker pack. The headbadge no longer had Johnson Engineering on it. The down tube and fork stickers had the new, non-lightning-bolt logo and on the seat tube was either a single “Chrome Moly” sticker or nothing in the case of the mild-steel frames.

The company had developed a reputation as a maker of some the best forks available at the time. Its forks were lightweight, featured neutral steering and had heat-treated steerer tubes and stress-relieved legs, making them popular with many racers and early freestylers, such as BMXA test riders Bob Haro and R.L. Osborn who had them on his SE Racing P.K. Ripper.

Building on its reputation, Torker added two fork sizes to the catalog filling voids in the burgeoning mini and 26-inch cruiser markets, despite not yet offering compatible frames.

The mini forks weighed 1 pound 4 ounces and were built with 7/8-inch O.D. chromoly tubing rather than the 1-inch used on the standard and cruiser forks. Over the years, Torker offered two sizes of mini forks. One had legs equal in length to the standard and fit tires up to 20 x 2.125. The other had shorter legs and barely fit 20 x 1.5 tires. It’s unclear when each was sold by Torker. Some Torker Factory Team members, among them Jason Jensen, raced on E.K. Replica frames with mini forks. In photos, his forks appear to be standard length minis. Confirming this is the fact that he used Mitsuboshi Competition II 20 x 1.75 tires in the front.

At least two Torker bikes were offered in 1979. The Maxflyte was Torker’s top-of-the-line bike. It came with an array of high-end alloy parts such as three-piece cranks. The 1980 Hutch BMX Racing mail order catalog lists the Maxflyte at $288.75. A year later, the price jumped to $318.75.

The Torkflyte, which was available in mild-steel or chromoly, was similar to the Maxflyte, but it had Takagi, chromoly, one-piece cranks. From Hutch in 1980, it cost $209.75 in mild-steel and $239.75 in chromoly. Its low price and solid spec made it Torker’s top seller.

The bikes came in all the Torker colors with contrasting anodized parts.

Also in 1980, Hutch listed a bike called the Torker Trashflyte, which cost $164.75. Other than colors, no information on the bike is listed in the catalog. The bike was probably one of the “street thrashers” that were sold at the time. Most “street thrashers” featured mild-steel frames, single-clamp stems, steel box-style handlebars and other entry-level parts.

Torker’s in-house bike line wasn’t the only one available at the time.

In the Jan./Feb. 1979 issue of BMXA, Everything Bicycles ran a full-page, full-color ad featuring the distributor’s own take on what a Torker bike should be—the $369.95 Torkflyte and the $495 Tork Pro.

“We took Torker frames and forks and make bike kits,” said Howie Cohen, Everything Bicycle’s owner.

“We bought special boxes and packed the bikes in them. One box took the frame, fork and wheels. Another box had the parts kits. We sold them as bike kits, unassembled,” he said.

The spec on both Everything Bicycles Torkers included: alloy bars, Oakley I grips, MCS stem, fluted alloy seatpost, Everything’s own PL-1-style seatpost clamp, Suntour VX cranks, Araya rims (7bs on the Tork Pro, 7Cs on the Torkflyte), and Mitsuboshi Comp II tires. The chrome and blue Tork Pro is pictured with Reedy pedals, unidentifiable small-flange hubs and a suede saddle, while the white and blue Torkflyte has KKT rat traps, large-flange hubs and a nylon saddle.

Besides the Torkers, the full-color, full-page ad also features two similarly spec’d Powerlite bikes and a third Powerlite street thrasher also spec’d by Everything Bicycles.

On the facing page of the Everything ad is a full-color Torker ad featuring a drawing of Eddy King by Bob Haro.

It was these ads that first attracted me to Torker. I fell in love with those colorful bikes—the Torkers with their twin top tubes, in particular.

After many hours staring at the ad, it occurred to me that, with the exception of the top tube, Powerlites and Torkers were almost the same—the forks, gussets, rear dropouts, even the geometry appeared to be the same. From that point on, I always associated Torker with Powerlite. A connection I would only verify while working on this article. By this time, however, Steve Rink was working with other sub-contractors and had no relationship with Torker.

“I’m not sure about any similarities between the two bikes. I know our forks were made with 7/8-inch tubing and I think Torker used 1-inch,” Rink said.

Throughout most of 1979 and into mid-1980, Torker continued to stamp serial numbers on the bottom bracket shells. As mentioned previously, serial numbers now had the additional ending of “M,” indicating that the frame was made with mild-steel tubing rather than chromoly. The serial numbers on Eddy King Replica frames ended with an “E,” which may or may not stand for Eddy. Because L.P. frames with European bottom brackets were available before King joined Team Torker, the “E” may have stood for European bottom bracket.

King said his personal bike had a special serial number. “I remember EK 1 was stamped on the bottom bracket,” he said.

Another change to the frames in some time in 1978 or early-1979 was the move from a round brake bridge to a flat plate bridge. Torker forks are still undrilled.

A line of Torker clothing and accessories such as pads and gear bags also was available.

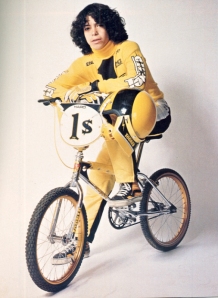

The Greatest Team In 1980, Torker’s team was the team. It included BMX Hall of Famers Eddy King, and Clint Miller (joined in late-1979) and Doug Olson, Jason Jensen, Doug Davis and Mike Aguilera. This is perhaps the team that Torker is best remembered for.

“Life on the Torker Team was a dream at the age of 13. I got to tour the country. It was an awesome experience. Steve Johnson was a great guy to be around. He was a great influence on all of the team members,” Aguilera said.

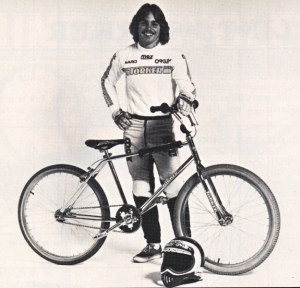

The Torker Factory Team was number one in 1979. (Left to right) Company president, Steve Johnson, and racers Mike Aguilera, Jason Jensen, Doug Olson and Eddy King. Doug Davis also was on the original team.

Bob Haro also was riding a modified Torker in his freestyle shows. Two years later, he would become Torker’s biggest frame customer.

The company and its racers were getting major coverage in all the major BMX magazines.

BMX PLus! interviewed and featured the entire Torker team and reported on Eddy King and Clint Miller’s bikes in its May 1980 issue.

In the June, BMXA gave the cover to Eddy King and Torker and devoted five pages to a pictorial of the popular rider. His chrome and gold bike was one of the most tricked-out on the race circuit.

Here’s a rundown of how it was built up: Eddy King Replica frame; Torker forks; Torker aluminum V-bars; Torker stem; Grab On grips; Tange headset; Shimano pre-bent brake lever; Shimano Tourney brakes; Mathauser Finned brake pads; 170 Campagnolo Gran Sport cranks; Phil Wood No. 3 bottom bracket; Sugino 44T chainring; filed KKT pedals; Suntour 16T freewheel; 36-hole Phil Wood hubs; 80-60-guage stainless steel spokes; Araya 7b rims; Cheng Shin 1.75 front tire; Mitsuboshi Competition II 1.75 rear tire; Cinelli Unicanitor saddle; Addicks seatpost clamp and a chromoly seatpost.

Eddy King’s personal bike had the yellow headbadge and the lightning-bolt Torker logo down tube stickers used on the pre-1979 frames. These stickers are sold today as part of SBS’s retro Torker sticker packs. They were not, however, standard on the Eddy King Replica frames sold by Torker.

King said his personal bike was basically a standard L.P. with a European bottom bracket.

“I think I had some input on the toptube length and the head tube angle,” he said, adding that he couldn’t remember why he ran the custom stickers.

King left Torker in October and joined the new Diamondback team.

“Torker was a great experience, but I saw that Diamondback had more money and better support. They had the budget to blow everyone else out of the water. I do wonder what would have happened with Torker if I had stayed,” King said.

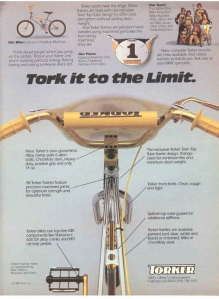

Torker received a big plug in the December 1980 issue of BMXA when the magazine tested the Maxflyte. The 12-page article featured an in-depth review of the bike, a peek at Clint Miller’s personal bike, a look at the team, which then included Miller, Jason Jensen, Cathy Hanna and Patti Gammill, and a bit of info on the company itself.

The Maxflyte that year was spec’d as follows: 4130-chromoly Torker frame available in standard, long or European bottom bracket (formerly the E.K. Replica) models in chrome, red, blue, white or black with blue, red or gold components; Torker forks; Torker alloy handlebars; Finish Line grips; Torker 6-bolt stem; 36-hole Araya 7X rims laced to Shimano freehubs with 80-guage spokes; Shimano Tourney brakes front and rear; Mitsuboshi Competition III tires (Not available at test time. Test bike had Competition II tires.); KKT Lightning pedals; 175 Shimano 600 EX cranks with One-Key Release; 44/16 gearing; Kashimax MX saddle; 4130-chromoly seatpost and an Addicks seatpost clamp.

Miller’s personal bike featured a custom fork (painted black) with special geometry for quicker steering, Cook Brothers chromoly handlebars, Haro Handle brake levers, Redline non-pinch Flight cranks with a Takagi spider, a Carlisle Aggressor MX 20 x 2.125 front tire and large-flange hubs.

A month later, in its January issue, BMX PLus! tested the Torkerflyte with Greg Hill as the test rider.

Bikes such as the Maxflyte were at the forefront of Torker’s marketing that year. A chrome and gold Maxflyte was featured in full-color, full-page ads in BMXA and BMX Plus. Like the test bike, it was spec’d with a full battery of Shimano components. Torker’s new stem (introduced in 1979) was front-and-center on the bike, as were its alloy handlebars, which were available in V- and straight-crossbar models. The company continued to tout its engineering prowess.

Torker added visors and Haro number plates to its clothing and accessories line.

By the end of 1980, the Johnsons started Max, which was run by Doug Johnson and produced a line of racing leathers, jerseys and other soft goods and accessories.

Starting in late-1979 or at the beginning of 1980, serial numbers were located on the inside of the right rear drop out and some forks are drilled for brakes.

Reversal of Fortune The year 1981 seems to be the beginning of the end for Torker. In the magazines, it appears to be as strong a company as it had been the previous three years, but it’s line was in a constant state of flux. Several new frames hit the market, but so did a line of components, most of which never caught on with BMXers or may have never even hit the market.

It was a crazy year for the BMX industry. Sales were strong and the small companies that dominated the market were experiencing rapid growth—growth that hurt as many companies as it helped. Other companies were beginning to look to overseas manufacturing.

Like many small BMX companies at the time, Torker may have been unable to react quickly enough to the market, or it over reacted, expanding its line too quickly, straining its financial and manufacturing resources to “the max.”

Despite what may have been happening behind the scenes, Torker continued to develop new products.

Torker introduced its first cruiser frame—a 26-inch model—and a mini frame that year. Both were available in a smaller color pallet than in the past—chrome or black. It also unveiled sealed European and American bottom brackets.

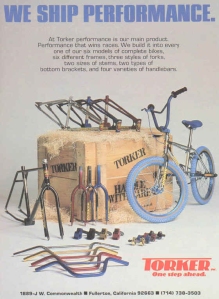

According to one full-color, full-page Torker ad, the company’s full line of products included “six complete bikes, six different frames, three styles of forks, two types of bottom brackets and four varieties of handlebars.”

The six frames probably included chromoly and mild-steel standard L.P.s and L.P. Longs, the 26-inch cruiser and the new mini, which took the place of the L.P. with a European bottom bracket (E.K. Replica).

It’s often said that the 24-inch cruiser was introduced in 1981, but it isn’t featured in the ad showing the Torker line-up and all evidence shows that the 24-inch cruiser hit the market in early-1982.

Doug Olson offered his recollections about the line. “In 1981, I think we were still making a mild-steel version of the L.P. The 24 came out at the end of 1981 because I was racing it,” he said.

“There was a Long L.P., which I thought was used for the 280X. I also made a few really long L.P.s with 4- and 5-inch longer front ends. I think I was the only one to race them, but everyone that rode it fell in love,” added Olson who, at 6-foot 3-inches, towered over his Torker teammates in 1980.

The new mini was featured in the April issue of BMXA in a story about 9-year-old racer Jason Jensen and his tricked-out bike, a black Torker mini with custom copper lacquered components. The frame, like the cruiser, lacked head tube gussets. It had a 17.5-inch top tube, 7/8-inch O.D. down tube, European bottom bracket shell and used 13/16-inch O.D. seatposts.

Jensen’s bike was spec’d like this: Torker 4130-chromoly, mini frame and forks; custom-modified Torker stem; Tange MX-5 headset; Laguna alloy, mini, V-bars with a 5-inch rise; Oakley .5 grips; Shimano Tourney brakes; Team Products, two-finger brake lever; Uni Seat; Tange seat clamp; Araya 7X rims; Shimano Dura-Ace road hubs with track axles; 80-60-guage, stainless steel, DT spokes; Mitsuboshi Comp II 1.75 front tire; Raleigh Red Dot 1.75 rear tire; 16 x 1.75 inner tubes; Suntour 16T freewheel; Sedisport 3/32 chain; Suntour MP100 pedals; 170 Shimano 600 EX cranks; O.M.A.S. bottom bracket with alloy crank bolts and a Dura-Ace 44T chainring.

BMX Plus also featured Jensen in a profile in its Sept. 1981 issue.

Torker’s other big product introduction that year, a 26-inch cruiser, made its debut in BMXA in the September 1981 issue when the magazine wrote about Clint Miller’s new bike.

The frame was built with larger-diameter 5/8-inch tubing (20-inch frames have 1/2-inch tubing) for the top tube/seat stays and the chain stays. The rest of the tubes were beefed up by a 1/4 inch to 1 1/4 inches. The wall thicknesses, were 30 to 40 percent thinner. In the 1981 Wes’ BMX mail-order catalog, the frame and fork cost $170.

Torker entered the new cruiser market in 1981. Clint MIller and his 26″ Torker cruiser were featured in the September 1981 issue of BMXA. In 1982, Torker discontinued the 26″ frameset and switched to a 24″ model.

Clint Miller’s 29-pound, 14-ounce bike included the 26-inch frame and fork; Tange headset; Torker stem; Prodyne cruiser handlebars; Oakley .5 grips; 36-hole Shimano large flange hubs; Ukai rims; 80-guage spokes; Dia-Compe, side-pull rear brakes; Mathauser brake pads; Shimano DX brake lever; Mitsuboshi 2.125 and 1.75 Silver Star tires; filed MKS BM-10 pedals; Redline non-pinch Flight cranks; 44T Addicks graphite sprocket and Addicks spider; 20T Shimano freewheel; HKK chain; Elina Lightning saddle; Addicks seat clamp and a chromoly seatpost.

At this point, all Torker frames still have flat brake bridges and serial numbers on the inside of the right dropout. Forks appear to have been available drilled or undrilled as both appear in photos throughout the year. In the April issue of BMXA (photos were likely shot the previous winter) Jensen’s mini has undrilled forks while Miller’s 26-inch cruiser forks in the September issue (photos likely shot in the summer) are drilled for brakes.

The new 26-inch cruiser serial numbers end with the letter “C,” presumably for cruiser. The mini’s serial numbers end with an “R.”

L.P. frames were still available in chrome, black, red and blue. The stems and bottom brackets came in red, blue, black and gold.

Torker also began building frames for Haro in 1981.

Chasing a New Market Nineteen-Eighty-Two was a year of big changes year for Torker, as well as the rest of the BMX bike makers.

As many serious BMX racers were custom building their high-end racing bikes rather than buying complete bikes off bicycle shop showroom floors, retailers were asking for less-expensive bicycles to meet the growing demand from kids who wanted BMX-style bikes, but who had no need for expensive race-quality builds.

For Torker, this meant the introduction of the 280, 280X and 340, three low-price bikes. The 280 and 280X chromoly frame sets are identical to the L.P. and L.P. Long, which no longer appear in Torker marketing materials. The 340 was a 24-inch cruiser.

BMXA tested the 280X in its September issue. According to the article, the name came from the suggested retail price of $280. Unlike their pricier predecessors the Maxflyte and Torkflyte, the 280 and 280X were spec’d with price-point components. In many cases, Shimano and Torker components were replaced with less-expensive Sugino or Sakae Ringyo (SR) parts.

The BMXA test bike looked like this: Torker 4130-chromly frame and forks; Torker chromoly Pro “T” handlebars; SR MS-240 stem; A’me Tri grips; Tange AW-27 headset; Araya 7X rims with Suzue large-flange hubs; IRC Z-1 tires; Dia-Compe 890 rear brake; Dia-Compe Tech 2 lever; MKS BM-10 pedals; 175 Sugino one-piece cranks with Sugino 44T chainring and spider; Suntour 16T freewheel; Torker saddle and SR fluted alloy seatpost.

Torker, however, didn’t forget about the high-end. Prior to the release of the 280 and 280X, Torker replaced its 26-inch cruiser with a professional-level, 24-inch frame set—now the standard size cruiser for racing. Many pros had started racing the new cruiser class the previous year and the smaller bikes were gaining popularity with amateurs and the general public. Like the 26-inch cruisers, they were available in chrome and black.

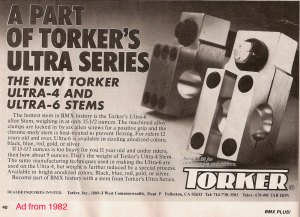

Torker also organized its growing component line under a new name—Ultra Series. All the components were machined by sub-contractors and assembled in-house, sometimes by Torker Factory Team members.

“Every time I flew into town, we were at the Torker Factory discussing racing strategy, and we sometimes would help assemble the Torker goose necks. It was great every time we got to visit the Factory. We always got to pick out any kind of part we needed for our bikes,” Mike Aguilera remembered.

Ultra Series components included the Ultra-6 and new Ultra-4 stems, sealed European and American bottom brackets and sealed bearing hubs. The hubs, which closely resemble Sunshine’s three-piece hubs, appear to have been sold in very small numbers. Only one set is known to exist.

The new, four-bolt Ultra-4 stem was similar to Jason Jensen’s custom-modified stem and made its appearance in the summer of 1982. They had the same dimensions of the Ultra-6 stems, but featured a split cap, 1-inch hole in the base and a shorter quill. Several non-split, four-bolt, stems also are known to exist. These are often considered to be prototypes, but this has not been confirmed.

Torker introduced its original 6-bolt stem in 1979. In 1982, it introduced a lightweight 4-bolt model and new brand name—Ultra Series. Other Ultra Series products included bottom brackets and a new hub set.

According to Torker ads, the stems, American bottom brackets and hubs were available in red, blue, black, gold and silver, while the European bottom brackets came in black, gold and silver.

Rarely seen and virtually unknown, Torker also dabbled in the new sport of mountain biking, building four Summit bikes. The location of one bike and one frame are known, while the remaining bikes belonged to the Johnsons until they gave them to friends several years ago.

“We had them on our motor home for years. I gave one to a friend for his kid to ride and the other to another friend on extended loan,” John Johnson said.

The known bike appears to be stock with the exception of the grips, saddle, tires and pedals. The bike features a Torker-made frame with an American bottom bracket shell, cable braze-ons, cantilever brake bosses and forks with standard Torker BMX dropouts. Among the components are a Torker Ultra-6 stem, Torker sealed bottom bracket, Torker chromoly mountain bike handlebars, Ambrossio rims, Galli hubs, Mafac cantilever brakes and a Suntour drivetrain.

“We made a handful of these things [mountain bikes] and I remember at that time I thought they were really ugly,” Doug Olson said.

Johnson said the reason they never made more was because mountain bikes at the time had silver brazed frames.

“We were welding our frames and we didn’t want to get into silver brazing. We didn’t think a welded frame would sell,” he said.

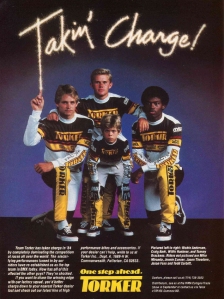

The Torker team was still finding success with Clint Miller in 24-inch cruiser and new addition Kelly McDougall, while Eddy Fiola was winning freestyle competitions on a Torker.

Torker’s marketing also consisted of ads in BMXA and BMX Plus promoting the component line. They were less-expensive, 1/4-page, black and white ads.

Torker started promoting the 280 with the infamous full-color, full-page Torker the Barbarian ad. It featured a shirtless Clint Miller covered in war paint a la Arnold Schwarzenegger in the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian.

Starting in September 1982, all serial numbers start with three letters as opposed to two and look like this: TYY 244 SC (24-inch cruiser) and TWW 2339 0 (280X). The serial numbers, perhaps for the first time, easily identify the frame model and the month and year it was built. Frames made in September 1982 have serial numbers that start with TZZ. The last frames made by Torker in Fullerton in September 1984 have serial numbers that start with TBB. To decipher a three-letter serial number, start with TZZ and go backward consecutively toward TBB. (TYY = October 1982, TXX = November 1982, etc.)

The new 24-inch cruisers have serial numbers that end with “SC,” which may stand for small cruiser. Torker stopped using the “L” at the end of serial numbers on its standard 20-inch frames (Now the 280.), but the 280X frame serial numbers still end with a “0” just like the L.P. Long. Torker-built Haro frames had serial numbers such as TNN 2185 F, with the “F” presumably representing “freestyle.”

Frame and fork stickers remained unchanged at the beginning of the year, but by the end of 1982, some frames had a new oval headbadge as seen in the September 1982 issue of BMXA. The following year, the 280 and 280X got totally new graphics. Frames were available only in chrome.

End of an Era To be honest, it has been difficult from this point on to track the Torker product line. Torker seems to have developed a split personality. It was developing high-end products for its racers, but was pushing its price-point bikes on the general public.

Close inspection of race photos featuring Torker Factory riders Kelly McDougall and Dave Marrietti show them riding the new Pro X frames, but Torker’s advertising was focused on the price-point 280. The ads were again high-production quality, full-color, full-page ads, but they featured arguably cheesy themes.

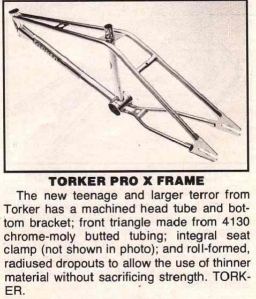

The Pro X, a longer frame set with a 19.5-inch top tube, made its debut in 1983 and was the frame ridden by racers such as Tommy Brackens, McDougall and Richie Anderson, but it got relatively little media coverage. Torker also rarely, if ever, promoted the frame in advertising, opting instead to put its marketing dollars into promoting the 280.

The frames got a variety of new features, some of them technological in character, others simply cosmetic. The Pro X, for example had a machined head tube and bottom bracket shell. The design innovation improved strength and helped prevent flaring.

Torker built the Pro X frames with Ishiwata butted tubing and replaced the fish-scale gussets with gussets under the down tube similar to those found on the Haro frames and Redline Prolines as early as 1978. The Pro X serial numbers ended with the letter “P” and looked like this, TLL 0125 P.

In August 1983, the 280 and 280X saw the first change to the fish-scale head tube gussets since 1978. Vertically oriented elliptical cutouts in the two gusset plates replaced the old round holes.

Torker began to alter its frame graphics in late-1982 and introduced a new oval headbadge late in the year. But this was short lived and was replaced by a “T” headbadge that was part of a totally redesigned graphic look used on all Torker frames from 1983 on.

Getting a handle on just what Torker offered in its 1984 line is not easy. Based on what can be seen in photos of racers that year, the line appears to have grown and evolved. But few ads or marketing materials have surfaced that clearly outline what the company offered.

Photos of a small (You might call it a mini.) bike under team racer Jason Foxe show a frame that, like the earlier mini, lacks head tube gussets, but unlike any Torker before it, seems to have a single top tube and an integrated seat clamp.

Another bike recently surfaced in a collection that shares some of the characteristics found on Foxe’s frame, but that definitely has a new style double top tube.

Instead of two tubes diverging from the head tube and connecting to a plate at the seat tube, the frame’s two tubes run parallel to each other until they wrap around the seat tube and become seat stays. No gussets or plates connect the two tubes.

Its serial number, TEE 1260 RP, shows that it was made in June 1984. The ending letters, “RP” are interesting in that they are a combination of the “R” used on minis and the “P” used for the Pro X. The frame shares some characteristics of both, but its size—it has an 18.5-inch top tube—puts it in between both frames.

The frame also has a 7/8-inch OD down tube and fork legs. The head tube is machined and there is an integrated seat clamp.

The sticker set on the frame is the new 1984 version where Torker’s traditional white, black and yellow logo received the addition of a red stroke. Pads and jerseys at this time also got this treatment.

The bike appears to have been sold as a complete. Besides the frame and fork, other Torker parts include Junior T Bars (25 inches wide with a 5 1/2” rise), four-bolt stem and Torker-stamped cable clamps.

The stem is nearly identical to the so-called prototype 4-bolt stems made a few years earlier. (See the “Torker Made Sweet Components” sidebar.)

Some Torker frames made during this time had round brake bridges. Torker frames were available in chrome or white.

It was at this time that Haro took its production off shore, leaving a hole in Torker’s fabrication business.

“Haro left in 1983 and by early 1984 was importing frames and later complete bikes from Anlun in Taiwan. Our job-shop cash-cow dried up,” said Harold McGruther.

John Johnson, however, diagreed. “We didn’t make a lot of money off Haro. Bob was a big help to us in the beginning. He helped a lot with design work,” Johnson said.

Yet, despite their close relationship and the fact that Bob Haro was a pioneer in the freestyle movement, Torker made little effort to enter the scene when it was starting to boom.

“The Johnson family was extremely slow to embrace the freestyle movement, too, even though their sister company Max leathers sponsored a bunch of freestylers like Mike Buff, Martin Aparijo, Woody Itson, Fred Blood. We built a freestyle prototype for Martin Aparijo in the summer of 1984, but the company filed bankruptcy four months later,” he said.

Aparijo’s two prototype frames are now in the possession of friend and fellow freestyler Woody Itson.

In the summer of 1984, Steve Johnson put together a top-notch team and went on a media blitz to promote the team and the brand. His push, however, came too late.

Super BMX magazine published an article on the new team in the November 1984 issue, but Torker was already headed for bankruptcy.

Clint Miller left Torker for Kuwahara in 1983, and was replaced shortly afterward by Tommy Brackens.

Mike Miranda joined Team Torker in January 1984, but left in September when the company was unable to pay him. Richie Anderson joined the team in July and left in November when the team was disbanded and Torker filed for bankruptcy.

Johns Johnson said Torker’s bankruptcy was the result of more than 10 years of losing money.

Johns Johnson said Torker’s bankruptcy was the result of more than 10 years of losing money.

“Torker was always a non-profit organization. By the time you paid everyone off, there wasn’t much profit left for the family. Doris and I worked for free.

“The big guys were getting into BMX like Murray and Schwinn and we couldn’t compete with them. We couldn’t lower the price. Now, I think we didn’t charge enough for our bikes. We never figured in the overhead. And we had a very expensive team. The ads alone cost a lot of money,”

Johnson said.

He added that he and his family saw the bankruptcy as a necessity.

“It was our planned exit strategy. You might say we were tired. We didn’t hurt a lot of people by going bankrupt. Most of our suppliers shipped to us C.O.D. and we paid our bank in full. We saw it was going to happen, so we bought extra parts for the Haro frames and sold those to Bob.”

The Post-Johnson Years

According to McGruther who was there, in November 1984, the owner of Seattle Bike Supply (SBS) bought the bankrupt company at public auction. “Bob Morales bought the Max name for $300. Seattle Bikes bought the Torker name for $3,000. I bought my wooden desk and office chair for $25,” he said.

Johnson said he didn’t remember how much money the auction raised, but it was insignificant. “We didn’t get much out of the bankruptcy. We paid our big creditor, the bank, and that was pretty much it,” he said.

Todd Huffman said he and Morales walked the auction and bought all of Torker’s excess parts inventory. “We got all sorts of components. I remember getting a lot of Torker stems and wheels. We used those to start a distribution company that eventually became Auburn,” he said, adding that all of Southern California’s local builders were there. “They were buying the jigs and tooling. Some of them were just walking around. I think everyone was in shock to see all that being sold.”

Morales said he wanted the Max name just to put it out of business. As the owner of Dyno, one of Max’s main rivals, he got a bit of a thrill buying his competitor for next to nothing and then removing it form the market.

Torker would quickly find its way into the hands of the Marui Brothers, who also own Tioga. At the height of the freestyle movement, Marui reintroduced Torker as Torker 2 with freestyle bike and frames like the 360 Flite and 540 Flite and a newly designed 280X, which were built by Akisu in Japan.Torker operated under Marui until about 1989.

In the mid-1990s and under new ownership, Seattle Bike Supply (SBS) reacquired the brand from Marui, an acquisition that reportedly cost SBS $1, and brought it back to life with a race team anchored by Matt Hayden and Clarence Perry.

“We had a relationship with Tioga because we used their tires. They weren’t doing anything with Torker, so we asked about it and bought it,” said Craig “Gork” Barrette, SBS’s marketing manager.

The high-end ST frames SBS sold under the Torker name in the 1990s were built in California by Mike Devit, who also was building SE frames.

The Torkers were built using 6061 T-6 aluminum with modern features such as 1 1/8-inch head tubes and cantilever brake bosses, but retained the dual-top tube design.

Torker also offered a range of low-end and price-point frames and bicycles, some with the double top tube, some without. The revival, however, was short lived.

Torker is now a beach cruiser and unicycle brand. At the 2008 Interbike Expo, the bicycle industry’s largest U.S. trade show, SBS unveiled the U-District, a single-speed bike for college students. The all-black, flat-bar road bike has the original Torker logo on the down tube and the Torker 2 headbadge.

Now owned by industry giant Accel Group, SBS also owns Redline, which has become the focus of its BMX business.

SBS does, however, offer a re-manufactured sticker packs for early Torker frames. Sticker packs for later models are expected to hit the market in the future.

The Johnsons Now. John, Doris and Steve still live in Anaheim while Doug splits his time between Sitka, Alaska, and Puerto Princessa the Phillipine Islands.

After John, now 86, retired from the FAA, he wrote inventory control programs and operated a billing service for about 10 years. He remains active with computers.

Steve, Torker’s president, went to work at Hughes Aircraft in Fullerton, CA. He retired after 20 years with the company.

Today, he enjoys spending time with his kids. His hobbies include photography and computers.

Doug built a home on Maui, Hawaii, and worked a number of years for the Parsons Company, which removes exploded and unexploded ammunition from the island of Kahoolawe.

After the bankruptcy and prior to this article, no member of the family spoke publicly about Torker. “No one ever asked, “ John said. “We thought everyone forgot abut Torker. —Michael Gamstetter

© Michael Gamstetter 2010

Original Article: https://fortyfour16.wordpress.com/torker-history/

Hi, I read your article and it was very informative. Thank you. I bought my torker as a frame and forks in the early eighties, and still have it. Was hoping you could help me w/ the ID # as I haven’t found a match to this pattern.

OT 4158 on the inner right rear drop out.

Would really appreciate your knowledge on this.

Thank you in advance. …. Bill.

Leave a comment